Under the eternal blue sky: Lessons from the period of the Pax Mongolica

The Mongol MessengerWhere land

and sky meet mind: reading nature’s signs as you travel life’s journey with no

borders to fence you in.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 9

out of 10 people around the world breathe polluted air. While the poorest

are hardest hit by this scourge, the wealthy cannot escape. In the Thai

capital, Bangkok, recently, hazardous levels of polluted air led to the closure

of schools for several days and drones were used in a vain effort to ameliorate

conditions. During the current 2018-2019 winter, Ulaanbaatar, the capital of

Mongolia, similarly confronts the serious problem of poor air quality reaching

hazardous levels without clear solutions in sight. On January 30th,

President Battulga, in an address delivered to the Standing Committee on

Environment, Food and Agriculture of the State Great Khural (Parliament) in the

State Palace; formally called for a state of emergency to deal with the crisis.

The new Prime Minister and The Great Khural are yet to respond.

It is clear

that in most parts of the world current problem-solving efforts to deal with

poor air quality have largely failed to provide citizens with clean air to

breath particularly those living in cities. Environmental sustainability more

generally seems as far out of reach as it has ever been.

The crisis

in the relatively small northern capital city of Mongolia, of some 1.5 million,

can be read as a microcosm of the larger global challenge confronting the

planet as a whole. It’s a critical mess

that has resulted from a heavy and intractable dependence on brown and black

coal, in particular, and fossil fuels in general. Humans have been on a journey

over centuries taking us further and deeper into a dead end gorge. We need a

way out. In this paper we will demonstrate the gravity of the air quality

crisis that has developed in Ulaanbaatar. Then we draw on nomadic and Pax Mongolica traditions to offer fresh ways forward, up,

over and out of the cul de sac to the taiga and ultimately onto the open

oceanic steppes beyond where we have a chance to breathe free again.

We do not

deny the vital role that science and innovative technology have to play, but

science and technological fixes alone are not sufficient. Sometimes, in fact, quite commonly, they may

actually exacerbate the problems. Essentially we believe that governments,

policy makers, bureaucrats, business leaders and engaged citizens will all

benefit by working together in collaboration, learning more from the past and

listening to the surviving present voices of the nomadic peoples of Central

Asia, and elsewhere in the world, who have stayed close to the land and the

sky. The ancient wisdom of indigenous

tribes and first nations peoples around the world has been devalued for too

long. Our think tanks and universities with their research specializations that

narrowly focus on particularities have their place, but we need synthesizers

too. We also need a revaluing of the concept of big history something the

Mongolians know something about.

Poor air

quality in Ulaanbaatar: The problem

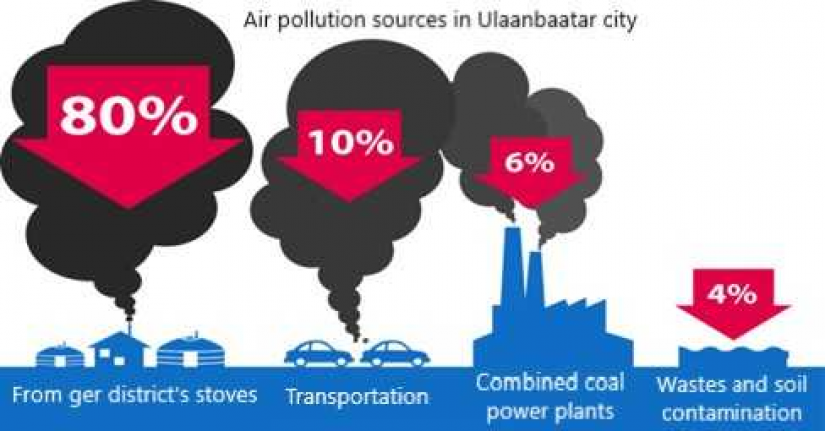

It is in the

winter period each year, for some five to seven months, when a large proportion

of Ulaanbaatar’s population living in ‘ger’ or yurt (traditional felt dome

shaped homes) districts, uses raw coal for heating purposes, that hazardous

levels of poisonous particulate matter in the atmosphere are reached. During

this time some 80% of the toxic particulate matter in the atmosphere in the

city comes from the burning of raw coal in the sprawling ‘ger’ districts of the

city where some 80% of the population live. At this time of the year when

respiratory and other medical conditions spike.

Source:

www.agaar.mn

Research

data shows that in suburbs such as Bayankhoshuu the poor air quality on some

days is a direct threat to the life, health and well-being of the population.

Source: www.agaar.mn

On these days’ residents of the capital don’t simply see

the thick smog and smell the tar smell of coal they can taste it in their

mouths and feel it in their throats. Recent reports, and documentary films, including Kate Buckley’s powerful 2018

film, ‘Mongolia: The World’s Dirtiest Air’ have highlighted the intractable

nature of the problem and the tragic personal stories of families with young

children who are vulnerable to sometimes fatal respiratory conditions.

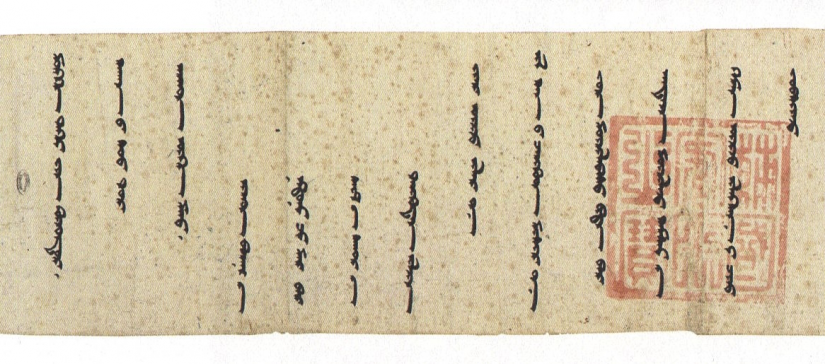

Mongolians are remembered as being skilled in the arts of war, little

is known about their skills in the art of diplomacy

To better

explain how we might draw on ancient wisdom we will return to the period of

Mongolian hegemony. This period is known as the Pax Mongolica and lasted for

about two centuries after the initial conquests of Genghis Khan. In late

November 1289 CE, arriving at the royal palace of the French king, Philippe le

Bel, at Fontainebleau in

the heart of Christian Europe, an emissary of a descendent of Genghis Khan, the

great Mongol leader Arghun-Khan,

from far-off Mashhad in Central Asia, carried with him a message. The emissary, Buscarel of Gisolfe, a Genoan Christian, who lived and worked in the

multiethnic Ilkhanate in Central Asia and who often travelled further afield in

the Far East on business, would likely have been multilingual. As the scroll was untied and unrolled before

the king, the ancient Mongolian writing script that had been re-introduced by

Chinggis Khan to the nation he unified generations earlier, a script that may

have ancient links back from West to East to the Aramaic language and the

earliest writing from Ugarit in Syria, was revealed. The opening lines,

following the tradition established by the great Khan himself, would have been:

"Under the power of the eternal

sky,

the message of the great king, Arghun,

to the king of France”

Here we are interested not in elaborating the geopolitics and struggles for power over Palestine, the wider Levant and Mesopotamia that were at the heart of this inter-continental diplomatic mission during the period of the Pax Mongolia. Rather, by adopting a hermeneutic approach we seek to uncover the submerged truths and learn from the insightful and surprisingly modern ways that the Mongol rulers were able to appeal across cultural, religious and linguistic barriers to acknowledge the reality of a universally shared natural world that sustains life for all. By drawing on the shared bonds people have in common that tie destinies together they found a way to overcome the divisive and limiting influences of varying and oft-times conflicting tribal, religious and politico-economic belief systems that bred mistrust and suspicion.

Khan-Arghun standing, Ghazan on

his shoulder as a child. Khan–Arghun maintained a Bhuddist outlook on life

until his death in 1291CE. His son Ghazan later adopted Muslim ways. Khan-Abaqa, a

Buddhist born in Mongolia, the son of Hulagu Khan, the founder of the Ikhanate is on horseback.

Rachid al-Din, Djami al-Tawarikh, 14th century. Reproduction

in Genghis Khan et l’Empire Mongol by Jean-Paul Roux, collection “Découvertes

Gallimard” (nº 422), série Histoire

The

intercultural appeals used by the generations of Mongolian leaders in

establishing administrative rule relied not so much on obeisance to an

invisible, avowedly all-mighty god or to specific deities but rather on an

acceptance of the profound truths that emanate from the wisdom of the earth,

water, winds, animals, birds, skies, the stars, the moon, sun and seasons.

Particularly, an appeal to the big blue sky and the need for the taste of

freedom and the feeling that you are alive that breathing clean fresh air can

give.

Big Picture

Systems Thinking

A number of

powerful concepts emerged to shape Mongolian thinking at the height of

Mongolian power in the 1200’s and 1300’s.

One of these was big picture thinking based on the realization that all

things, both inanimate and animate are interrelated and that a sense of agency

and power can be had if you respect and tap into the cosmic energies of the

universe. The big picture view of history is available only to our species on

this planet and each generation with capable leadership can seize the day and

act on this realization. But robust,

communal orientated, inspired leadership is required.

By being

unafraid to look for wider frames of reference and refusing to be restrained by

inhibiting physical borders and mental boundaries it can be seen that some

aspects of the mindset of Chinggis-Khan himself, and that of the succeeding

generations of Khans including the great Khublai-Khan who united the Chinese

and founded the Yuan Dynasty in Peking and Arghun-Khan in the Central Asian

Ilkhanate, are seminal to and reflect attempts to apply, concepts now emerging

from the contemporary historiography

known as ‘big history’ such as that described by David Christian in his TED talk in March 2011.

The

well-known historian and translator Dr. Manaljav Luvsanvandan has pointed out

that the universalizing tendencies evident in the Pax Mongolica were a

precursor to modern globalization. The Internet we use today reflects the

crisscrossing rapid information flows built upon fast horse power networks

across Eurasia. [Personal communication with Dr. Manaljav]

So how might this mindset be applied to the current crisis of air quality in the capital city, Ulaanbaatar? We advocate for a multidisciplinary systems approach that draws on a key awareness of symbiotic webs of life within and across both the natural sciences and in the human realms including social, economic and political life. All healthy life is dependent the rocks, soil, water, sunshine and air as the elemental fundaments. In the human realm the Mongolians have had for eons the lattice-like infrastructure of the frame of the traditional ger [yurt] which serves to this day as a metaphor capturing the complexities, patterns and interrelated neural pathways as represented in the natural world, in the social world and in the individual human mind. Specialized professionals in universities and leaders in government and business all cocooned and separated from each other in their own worlds, overly concerned about their own micro level problems and pursuing their own vested interests really need to be brought together with the shaman, community leaders, poets, artists and ordinary citizens, young and old to meet, mix, listen, collaborate, rethink, plan and execute new problem-solving strategies. In particular, we advocate listening to mothers with new-born and young children.

Mongolia has

always been open to ideas and influences. These items are currently available

for sale in the huge Naran Tuul open market in Ulaanbaatar. Photo: the

authors

There is a

long tradition still popular in Mongolia today, of climbing a mountain to gain

a better understanding not only of the world below but of oneself. Looking down

as if from the sky above gives you great perspective and helps you to better

chart your direction ahead. Big blue sky thinking is needed now more than ever.

By Saruultur Bayarsaikhan, Mongolian Energy Economics Institute, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia and Mark Gillespie, University of Sydney, Australia, currently Visiting Lecturer, Foreign Languages Department, National University of Mongolia

Ulaanbaatar

Ulaanbaatar