Akim Gotov: Mongol Scholars Stand at the Roots of the Modern Translation Theory

Society

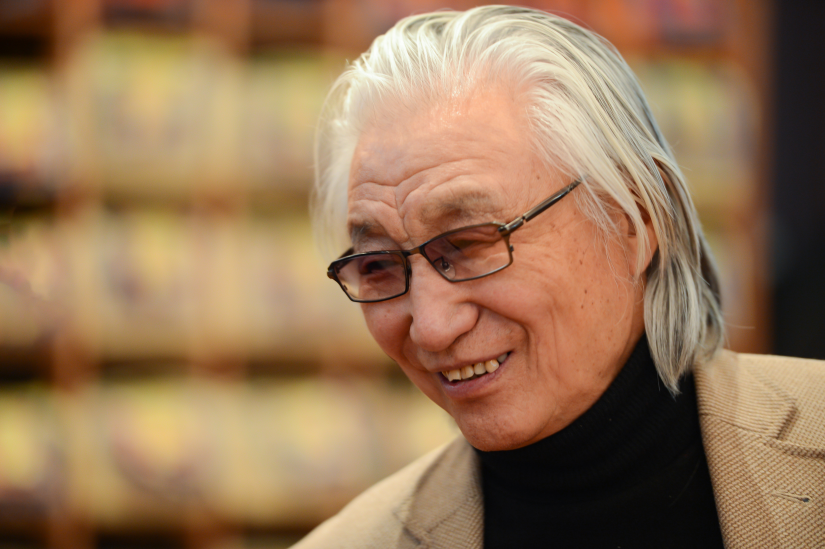

Ulaanbaatar, September 20, 2024 /MONTSAME/. Under the auspices of President of Mongolia Khurelsukh Ukhnaa, the National Forum of Translators of Mongolia will take place at the State Palace of Mongolia on September 30, 2024. In this regard, we present an interview with Mr. Khatagin Akim Gotov, an Honored Culture Figure, renowned Mongolian journalist, translator and researcher, a recipient of the prestigious literary award, the Rinchen Award.

-Thank

you for accepting our invitation. It is a matter of great honor for me to speak

with you today. Mr. Akim, you have very rare among the Mongols a name. What

does Akim mean?

-I was born during the Khalkhyn Gol battle, a wartime. A

midwife named Daagii assisted my mother’s labor, and apparently, she named me

Akim. I wanted to know the reason I was given this name, and when traveling to

Matad, I tried a number of times to meet with her, but every time she would be

gone to either Khalkh Gol or some other soum, and we never crossed paths. So I

never had a chance to inquire her of the reason why she chose this name for me.

Speaking in general terms, the names Akim, or Yakim are biblical names adopted

in Russian language, meaning soyorkhol, or blessing, granting, honor. When I

worked for Il Tovchoo newspaper of MONTSAME agency, at times when I would write

articles of dissenting views, I would use that name “Soyorkhol” as my

pseudonym.

-In

Mongolia there is a common tradition for fathers to give names to their

children, but your story also interesting. For every person a conversation

about fathers is dear and heartwarming. What qualities and features of your

father did you inherit?

-My father became a teacher after completing primary

schooling in Byaruut. Having taught at the Bayan-Uul soum school for 2-3 years

in modern-day Dornod province, he returned to his birthplace. He was one of the

first teachers of Mongolia of early 1940s, a time when not many children

attended schools. He would go around the neighborhood asking parents to let

their children attend schools. He was a father like any other. When I was in

the second grade, he brought me a book “Chuk and Gek” by A. Gaidar to read.

Later, in my 4th or 5th grade, he brings another book, one of the volumes of

Stalin’s works, a thick brownish book. He says, read it. I did. I read it for the second time, then for the

third.

Couldn’t understand anything. It

talks about Bolshevik something. I tell my father I understand nothing. Father

asks to read one more time. After many years, thinking of this incidence, I

realized one simple truth – my father wanted me to learn to read. To read fast.

Now when I read a book, I do not read letters and words. At a glimpse I catch

all I need from the text. This is one of the most precious gifts, the most

valuable lesson my father taught me.

-Inarguably teachers are as important as parents in

one’s life. They guide us in life through twists and turns of the destiny. You

regard the renowned scholar Rinchen Byamba as your teacher. But you never met

him in person and only twice had phone conversations.

-A famous novel by Sholokhov “A Man’s Destiny” was published in newspaper “Unen” when I was an eighth-grader. This was the first time I read a novel translated by this great man. A year or two earlier, I had read his novel “Uuriin Tuya”. I had already started waiting for his new works to be released. Reading him since childhood I grew up admiring him. I remain a passionate admirer. He remains my lifelong idol and role-model. When working on “The Gods are Athirst” by Anatole France I couldn’t translate two words. Timidly and humbled I called Dr. Rinchen. I told him I wanted to ask for some advice on translating two words into Mongolian, and having heard them the man said he needed to refer to a dictionary. He even didn’t ask my name. “The word you asked is close to Prior Lama in meaning”, having said that, he started a long explanation of this interpretation. The longer he spoke, the lower his voice was becoming, so I tightly glued the phone receiver to my ear trying to catch every word the man said. He was truly invincible. Nothing had bent him. He never yielded to years-long ideological attacks. Humiliation and slander never could discredit him. He remained strong, unbending and never apologized which communists wanted so badly. His invincibility, fortitude of will and mind are indomitable. I admire these his qualities and strive to live up to them.

-When talking about the learned man Rinchen, books,

translation I am tempted to ask for your advice for young people on how to

instill love to reading?

-It is hard to develop this allegiance in people who did not read much until adulthood. However, the case is different for children. The earlier children start to read the better. It is the duty of parents and teachers to help children develop reading skill and habit. As a second grader I read Chuk and Gek. Then I got a book titled “Brave Mountaineers” by Nadmid, about children who went hiking in the mountains but got lost. As I think of it now, maybe that book instilled in me the interest to climb and comb mountains and valleys I am so much fond of. I never met the author Nadmid. There was a janitor, a fine old man, when I worked for the Union of Mongolian Writers. I would occasionally see the janitor and we never got to speak with each other. I learnt later, to my deepest regret, that this man was Mr. Nadmid, the very author of my most favorite book. It pained me very much that I missed a chance to thank him for the book for he had already left this mortal world. This acute sense of regret still pinches me.

-You dedicate all

your knowledge, heart and efforts to the good of Mongolia, to discovering and

introducing the beauties of Mongolia. One of such hidden treasures of Mongolia

are rock paintings. You have been studying the petroglyphs for quite many

years. How did it start?

-It all started with mountains. I

headed to mountains. I wanted to write about worshipped mountains along with

various legends and myths associated with them. I thought that could help young

people learn more about their homeland. If I found out and described how

mountains were sanctified and worshipped, people would understand the nature

better and begin caring for and loving our motherland. It is my conviction that

learning and caring about the place we are born would instill patriotism.

Therefore, I wrote two books about mountains with all legends, myths and

worship rituals and traditions. And when climbing, studying the mountains I

discovered rock paintings! I was immediately drawn into them. The depictions

were truly enthralling: they told stories about day-to-day life of humans, but

most interestingly, I found images which could be defined as extraterrestrial,

unearthly mythical and empyrean. So I began my quest into rock paintings. Thus

far, I have written some 4-5 books on this subject.

-How different are the petroglyphs in Mongolia from

those found in other countries?

-Actually the rock paintings are

found mostly in Mongolia. Few have been recorded in Kazakhstan and Ural. Some

paintings and engravings are found in Altamira Cave in the Northern Spain.

These are few records that I have found out to date. In the cave in the Tonkhil

soum of the Gobi-Altai aimag of Mongolia there are dozens of such paintings

similar to the ones found in France and Spain, including palm painting.

-The palm painting sounds interesting.

-Indeed, interesting. Human hands are

our primary tools. You can’t do much without hands. I do not have any

scientific interpretations. I have explored most parts of Mongolia. In the

Gobi, almost every rock has paintings on it. Many are found in the Altai Ranges.

Only do Kazakh and Kyrgyz scholars and researchers present at international

conferences on petroglyphs, in other words, only the countries with rock

paintings study them.

Mongolia is a country of rock

paintings. It is the center of petroglyphs. The Del Mountain of the Dundgobi

province is entirely in rock paintings, all depicting daily activities of

prehistoric people. Some paintings are

just jaw-dropping such as the one in Lovon Ranges in Bayan soum of the

Gobi-Altai Mountain depicting a wild goat with a single horn. Nowhere else on

earth such a painting has been found.

A friend of mine called me recently

from Tonkhil soum of the Gobi-Altai aimag and said he had seen a wild goat with

a single horn, so soon I am heading to Gobi-Altai and really keen to factualize

this. The age of the painting is established by incrustation. The paintings of

the stone age are barely visible whereas those of the later ages, for instance,

the Turkic period, are very clear. However, it is hard to establish the exact year

these images were created. But the earliest are found in the Gobi.

-Mongolians know you as a renowned translator, and I am

extremely excited to talk about translation with you. You have translated a

great volume of world’s classical literature into the Mongolian language. Of

your masterpieces, the translation of “One Hundred Years of Solitude” by

Gabriel Garcia Marquez stands out. Why did you choose to translate this very

complicated novel, and how difficult was it to translate?

-Long before translating, I had

already read the novel. I had a famous translation Amar as my teacher. Those

were the times when the Soviet Writer’s Union would approve the list of foreign

authors to be translated into Mongolian. My teacher Amar was the Senior Editor

of the central editorial board at the Ministry of Culture and told me to

translate the novel. Yes, it was a hard job to translate it. The intertwined

stories involving numerous Buendia were truly confusing. I would often find

myself lost among those Buendias, and would start tracking their paths from the

start over and over again. The novel was totally alien to the Mongol mentality,

Mongol way of living. So, my goal was to present it to the Mongolian audience

preserving the original identity of the novel. I did translate, but can’t

really tell how well I did. It was received by the readers. Baabar once

complimented my translation: “I read the novel 4-5 times, but finally

understood it only in Akim’s translation”. To me this was a great appraisal,

especially when given by such a notable intellect as Baabar.

-How long did it take to translate it?

-Six months. I translated the “One

Hundred Years of Solitude” and Plaha” [“The Place of the Skull”] by Chingiz

Aitmatov concurrently. I managed to complete both translations within six

months. Back in this years, members of the Mongolian Writers’ Union were given

one month paid leave, not for vacation but for literary works. I secluded

myself in Selbe resort to work on Marquez’s book, but would spend half of my

time in Songino resort to work on “Plaha”. So running between the two, I

finished the two translations within 6 months. I was young and would work

through nights. I was both physically strong, and passionate. Some said I

worked like a machine. Once I open a book, I would literally by glued to my

chair for hours.

-Another remarkable work of yours is the translation of

the “Black Legend” by Leo Gumilev. There were times when the world ignored the

truth about the Mongols, about their role in shaping the modern world. Most

available literature was full of fiction on how disastrously destructive the

Mongols were. The “Black Legend”, contrary to popular belief, shed light on

truth.

-There is a context to that

translation. Writer Byambaa born in Choibalsan soum of Dornod province was then

a diplomatic officer in our Embassy in the USSR. The Mongolian diplomats once

invited Leo Gumilev for a lecture at the Embassy. L. Gumilev gave his

manuscripts to Byambaa and asked to translate. Byambaa then sent the text to me

saying that I should translate it. Shortly afterwards, Indra, the daughter of

Dr. Rinchen, received another copy of the book and gave to me for translation.

So I ended up with two copies of the same book. And, I did translate it.

-I heard that Leo Gumilev himself approached you while

on a visit in Mongolia and personally asked you to translate.

-Oh, another myth is emerging then

[laughs]. That never happened. I received copies of the original from Byambaa

and Ms. Indra, and I still keep them both.

- One of the essential sources on the

history of the Mongolian Empire is inarguably Jami al-tawarikh (“Compendium of

Chronicles”) by Rashid al-Din. Some sources indicate that it was written with

the help many foreign historians including Bolad Chingsang who was specially

invited from the Yuan Empire. This is a valuable historical account which talks

about events some of which are not mentioned even in the Secret History of the

Mongols, including a mention of the “Altan Devter” [“The Golden Book”] not

found to date. Written by multiple authors Jami al-tawarikh remains one of the

first major efforts of world historiography.

-The book was translated by the best Russian translators

from Persian. When writing a book about my own place of birth, I was searching

for information on Khatagin tribe in the “Compendium of Chronicles”. It had

been translated by Surenkhorloo guai from Russian to Mongolian. I looked up

through both the Mongolian and Russian translations of the chronicle, but did

not get much to understand. A while later I found an English version translated

by an American translator W.M. Thackston. This was an impressive translation.

The Russian translation was not much resourceful and omitted clearly Mongol

words taken by the translator as Persian or Turkic word. However, the English

translation was a diligent work. It had explanations of all terms and

vocabulary. So I decided to translate from English hoping that one day someone

would translate from original Persian.

I did not literally translate the

title as the Compendium of Sutras, instead I used the word “shashdir”, or

shastra. In Buddhist religion there are two central systems – Sutra and Tantra.

Sutras are teachings of profound meditation and yoga whereas Tantra is a form

of profound knowledge into the nature of the genuine ability of the mind. If I

were to translate the title as “The Compendium of Sutras”, the book should be

talking about meditation, which is not the case. This is a chronicle about the

Mongol Khaans. Shashdir or Shastra is a chronicle, historical account,

therefore Mongolian title in my translation reads “Shashdriin Chuulgan” [trans.

“Compendium of Chronicles”].

-You then had translations in Russian and English. Which

version did you keep as the main source?

-English. But I was checking against

the Russian, and found some discrepancies and mismatches. Therefore, I included

two versions of those particular unmatching texts, as translated from Russian

and from English respectively. This is my understanding of academic

translation, so I followed this principle.

-What are your thoughts about young translators of

today? I read a new translation of “The Headless Horseman” by Mayne Reid. To

me, it did not surpass the earlier translation released a few decades ago.

-Our young translators have mastered foreign languages impeccably. Many of them speak foreign languages as fluently as native speakers. This is also due to the fact that phonetically the Mongolian language can produce any sound of any foreign language. Therefore, the pronunciation of Mongolians is this much clear. For instance, there is no sound [r] in Chinese, but the Mongolian language has. Our own native language is very much resourceful and conducive to learning foreign languages. Written translation and verbal\oral interpretations are different. I regret to say that being fluent in foreign languages, some Mongolian youth does not possess our native tongue well. Without mastering the Mongolian language stylistics, translation is impossible. Some young people obviously lack this critical knowledge, hence, they tend to do word-by-word translation.

Of course, such rigid texts would not

read well and cannot be understood. Therefore, the youth must learn syntax,

stylistics and discourse analysis well enough before starting to translate texts.

Once I was studying Dr. Rinchen’s translation of “The Silver Prince” by A.

Tolstoi comparing it with the original. In the text I read a sentence which I

could have never translated the way Dr. Rinchen did. So, I copied the sentence

and took it to translate to Choijil, my dear friend, though a bit senior to me,

in a way, testing him. He translated the sentence in an instant. There were

only 2 or 3 words different, but the stylistics was the same. This incidence

made me even more convinced in the existence and power of the stylistics of the

Mongolian language. Stylistics is the fundamental knowledge that must be learnt

by not only translators, but also by all writers and journalists.

-Which of your translation works do you consider your

best piece?

-I consider my translation of the

“Scarlet Sails” by A. Grin [“Алые Паруса”, А. Грин] to be my best translation

work. It is not lengthy, but I spent three years on it. I think this was a

literary translation. In terms of presentation, my “Dog of the Heaven” was

written well. It was printed 6 times, but became a rarity among booklovers. I

heard its pirated copies were sold door to door in Inner Mongolia in Mongol

script.

-Sometimes I feel the personal character of the

translator is reflected in the translation. Translations of Dr. Rinchen, of Mr.

Amar, of yours, are all very different. What are special features of literary

translation? What translation is considered a good translation? What books

would you advise translators to read to improve translation skills?

-Translation does have a theory. The

earliest theory was established by Martin Luther, a German priest, in 1500s.

Martin Luther translated the Bible from Latin to German. In those times, Bible

and other religious texts were considered the words of God, and therefore, were

translated word by word as no one could dare to change God’s words. Martin

Luther developed a theory by which he translated the text accessible to lay

people. Later, in 1741 under the guidance of the Janjaa Khutugtu Rolbidorj of

Inner Mongolia, some forty Khalkha learned men and translators came together

and wrote an encyclopedia on Buddhism “Merged Garakhyn Oron” [“The Space for

Attaining Wisdom”] to translate Ganjuur Danjuur [Kanjur known as Buddha’s

recorded teachings, (or the Translation of the Word), and Tanjur is the

commentaries by great masters on Buddha's teachings (or the 'Translation of

Treatises)]. This encyclopedic dictionary outlines 21 translation principles. I

do have Martin Luther’s theory on paper but didn’t read it for it was written

in medieval German language which our German translators were not able to read.

So, as far as I know, the first

academic work on the theory of translation is “The Space for Attaining Wisdom”

written by Mongols. These 21 principles fully match modern theory on

translation. Modern translation theory was developed by V. A. Zhukovsky

(1787-1852, a famous Russian poet, translator) and some other Russian writers

and scholars in 1920s. There are also theories developed by American scholars.

But they all appeared later, and I proudly and confidently state that it was

the Mongolian scholarship which laid the foundation to the academic discipline

of translation in the world. I did translate those 21 principles into Cyrillic

and published with some explanatory notes. Those who are interested in the

theory of translation must have read the book. Translating without knowing the

theory can be identified with riding a horse without a bridle in an open

steppe. In the 1960s I wrote a book “Unlocking the Chest of the Art of

Translation”, I would recommend the interested youth to read it.

Translation is all about transformation: lexical transformation, grammatical transformation etc. It is a transformation theory. In Russian adjectives appear after the verb, in English too, however, in Mongolian they appear before the verb. Translation deals with ways and methods of transforming linguistic structure and presenting to the readers in a comprehendible way. In my book I describe the main methods of transformation.

-You said you wrote the book in the 60s, were you

teaching then? I noticed that not much Mongolian literature is being translated

into foreign languages.

-I wrote the book when was working in

the journal “Issues of Peace and Socialism”. Responding to your second

question, I must note that to be translated into other languages, the works of

our writers must draw the attention of foreign audiences. Also, there aren’t

many people to translate into other languages. There aren’t foreigners

proficient in Mongolian either. During the years of socialism, socialist

countries such as Bulgaria, Democratic Republic of Germany and others used to

periodically translate Mongolian literature, now this tradition ceased to

exist. Individual translators do translate at private requests and orders,

however, if there is no market, such initiatives will eventually die out. If

the country wants to advertise itself internationally, the government should

make efforts to accommodate this need.

At the same time, we must study very

carefully what Mongolian literature the foreign audiences would be interested

to read. Only then, when the Mongolian literature is rendered to

English-speaking audiences, or to German readers as if originally written in

those languages, will it touch their hearts. Dr. Rinchen’s translations of “The

Silver Prince” and “Taras Bulba” are truly outstanding works. I checked both

translations, word by word, against their originals. I made many notes. If

those who know Russian follow my suit and crosscheck the translations, that

could truly be a revelation and a genuine learning about the Mongolian language

and translation techniques. There are many brilliant translators of 1960-70s –

Shatar, Amar and many others, but, of course, Dr. Rinchen is unsurpassable. Not

only did Dr. Rinchen master Mongolian language, but also had an inborn talent.

He is a writer and poet. These natural endowments made him a great translator.

There was an Editorial Board of Literature at the Ministry of Culture, where

the renowned editors Shuger, Amar and Samdan worked. Their pens would turn our

translation manuscripts literally red. And that would eventually birth good

books.

-You translate, write books and study rock paintings.

Are you a scholar, or journalist, or a translator?

- I am a journalist.

-Of your journalistic works, which pieces are especially

close to your heart?

-I am humbled to talk about myself.

It was Dr. Rinchen and also translation which drew me into journalism. These

days I mostly write my travel notes. Travel notes significantly expand our

knowledge. For instance, notes on travel to Beijing would not be valued much if

I write about modern buildings in the city. I try to embed the cultural

features into my writings. I try to render knowledge in and between the lines

of my notes.

Or, for instance, if I write about

Tsambagarav Mountain [magnificent snow-capped mountain in the Altai Ranges in

Western Mongolia], I try to describe it poetically so that readers get

aesthetic appreciation from the piece. I would also enrich my presentation with

interesting legends and myths about the mountain. Legends are extremely

interesting. I once wrote that legends do reveal the truth. They do carry

truth. Westerners no longer consider legends as fiction. Truth, transcending

space and time become legends. For

instance, the westerners have begun writing that Zeus and other gods came from

cosmos. It is absolutely engrossing to find men in spaceships and spacesuits in

numerous rock paintings!

Fascinated by these discoveries I

wrote a book titled “Tracing the Footprints of Those Who Came from the Sky

Through the Toy of the Heaven’s Children”. That book is not a fiction, in other

words, I did not make it up. There are petroglyphs, and numerous research

articles and publications by foreign scientists and scholars who study cosmos

and space. To write that book I read about 10 books by Russian authors and

another 20 by British and Americans. Once a visited a family at the eastern end

of the Bayantsagaan Ranges in Bayankhongor province. In fact, I was travelling

in that neighborhood studying the mountain. One day, when I was taking photos

of a deer stone, a housewife of a ger in the vicinity approached me and asked

what I was doing. Of course, I responded that I was studying and taking photos

of petroglyphs, to which the woman said that her fathers and forefathers

forbade their children to even get close to those paintings for those were the

toys of the children of the Heaven. That encounter inspired me to title my book

after the toys of the children of the Heaven. It’s truly amazing, for instance,

at Chuluutyn Gol of Arkhangai province there is a painting of a rocket hitting

a deer.

-In one of your articles you claimed that homo sapiens

did not evolve from primates, for even the number of chromosomes aren’t

matching. You are a materialist or an idealist?

-I do not know much about “isms”, but

think that it is much better to be an idealist.

-You established and were the Chief Editor of “Il

Tovchoo”, one of the most popular newspapers, especially among intelligentsia,

in early 90. How would you define a journalist?

-A journalist must always steer clear

of money. If journalists start writing for money, truth will be lost.

Therefore, the first and foremost value, to never be traded at any cost, must

be truth. Journalists shed light on the darkest corners of the society, they

reveal the bad and evil of the society. If this duty is ignored, he or she is

no longer a journalist. A genuine journalist is the one who tells the truth.

- As for newspaper “Il Tovchoo”, it

was established under MONTSAME. The then Director General of the Agency Mr. S.

Bayar proposed issuing a Mongolian version of “Za Rubejom” to cover most

interesting international events and developments to which I responded

suggesting to issue a newspaper to cover Mongolia the way “Za Ruberjom” covers

the world. That was the time when MONTSAME was a part of the State Radio and Television

Committee. I was appointed the Chief Editor of the central editorial board for

the Committee overseeing the newspapers in Chinese and Russian, “Il Tovchoo”

and all other print media under the Radio and TV and MONTSAME. This way I came

to be associated with MONTSAME. Those were trying times for not only our

newspapers, but for the whole country. Mr. Erdene, the successor Director

General, one day called me and said that the Government wasn’t happy with a

newspaper which criticized the Government. So I took “Il Tovchoo” away from

government and made it one of the first free media of Mongolia. The title “Il

Tovchoo” was given by the renowned Mongolian write S. Erdene, and it means “The

Open Chronicle”.

-What translation are you working on these days?

-I finished translating the first

volume of Ata-Malik Juvayni’s Tarikh-i-Jahangushav, which is known as the

History of the World Conqueror. I am yet to complete the second volume. Also I

am compiling a book on the writings of the Mongolian learned men on space

studies. This would be the continuation of my book “Tracing the Footprints of

Those Who Came from the Sky Through the Toy of the Heaven’s Children”.

Some 139 geographic sites are

mentioned in “The Secret History of the Mongols”. I travelled to all of them. I

wrote a book on these travels, it is ready yet the hardest part is remaining –

to locate the photos, which I have in thousands. Once these three projects are

complete, I will consider my lifetime mission as complete.

-Many think of Mongolia as a paradise on earth – we

enjoy peace, freedom, pristine nature, and I fully concur with this definition.

It is our collective duty to strive to leave this beautiful country intact and

unblemished to our children and their children.

-The eternal blue skies are above us. The mother nature embraces and cuddles us as children. Many people ask where the motherland begins. If it begins, it should end somewhere. Well, to me, motherland has no beginning, and no ending. As long as a Mongol lives on earth, as long as his heart and mind are alive, Mongolia will dwell eternally. Some may ask, then, where the native land begins. Of course, it begins with your birthplace. For me, it begins with the sacred mountains.

Ulaanbaatar

Ulaanbaatar