The changing world of Mongolia's boreal forests

The Mongol MessengerContinued from the previous issue

Insects that eat leaves and needles

are, however, causing increasing damage in Mongolian forests. The Siberian silk

moth and the gypsy moth are the most destructive. Their caterpillars eat young

leaves, weakening and killing even healthy trees.

“In some areas the trees are totally

gone – there’s no recovery, the trees are all dead. The infestation area is

getting larger and larger.”

As in

other parts of the boreal region, the magnitude and severity of pest epidemics

has increased, says Oyunsanaa, and outbreaks are happening at latitudes and

altitudes that weren’t previously affected.

The impacts of climate change, fire

and pests are cumulative, says Werner Kurz, an ecologist at Canada’s Pacific

Forestry Centre in British Columbia. He’s an expert in the major boreal forest

pest there – mountain pine beetles – as well as a contributing researcher to

the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Warmer winter temperatures can enable

pests to expand their range, Kurz says, while drought and water stress make

trees more susceptible to insects. Where pest infestations kill large numbers

of trees, fires burn more easily and intensely – and release more carbon.

Kurz has seen the results for himself

in the Canadian boreal forests. “After the fire passes through, there’s no more

organic matter on the forest floor. Many of the standing trees are blown down

by the wind-storm generated by the fire, and the material on the ground is just

a white line of ash.”

“That has huge implications for carbon release, and for the water-holding capacity of the forest floor.”

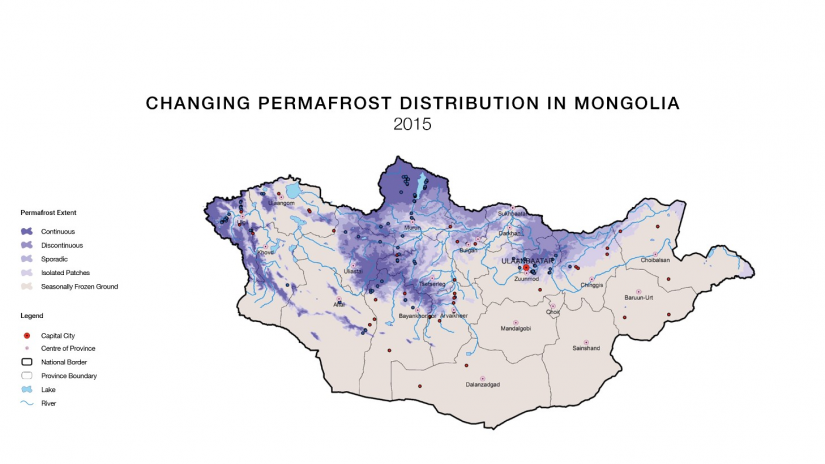

As temperatures climb, Mongolia’s

permafrost is shrinking, too. Permafrost is ground, rock or soil that remains

frozen for more than two years in a row. In Mongolia, it’s found across the

country’s north, over much the same area as the forests.

That’s no coincidence – in arid

regions, permafrost can increase the amount of moisture available in the

ecosystem, says Yamkhin Jambaljav from the Institute of Geography-Geoecology at

the Mongolian Academy of Sciences.

“The complicated interaction between

the forest and the permafrost maintains stable conditions in the ecosystem,” he

says.

To measure the extent of Mongolia’s

permafrost, Jambaljav and his team covered 24,000 kilometres over several

years, as they criss-crossed the country. They drilled 120 holes of up to 15

metres into the frozen ground to measure the temperatures beneath.

They found that five percent of Mongolia’s permafrost – 13,150 square kilometres – had thawed completely between 1971 and 2015.

The thaw is caused by climate change – but also amplifies it.

Plants and animals have been living

and dying in the boreal region for thousands of years. Where the ground is

frozen, it prevents their remains from decaying, storing the carbon in the soil

and keeping it out of the atmosphere.

But if the soil thaws, microbes

decompose the ancient carbon and release methane and carbon dioxide.

It’s estimated that the Northern

Hemisphere’s frozen soils and peatlands hold about 1,700 billion tonnes of

carbon – four times more than humans have emitted since the industrial

revolution, and twice as much as is currently in the atmosphere.

In 2011, scientists from the Permafrost Carbon Network estimated that if they thaw, that would release around the same quantity of carbon as global deforestation does –but because permafrost emissions also include significant amounts of methane, the overall effect on the climate could be 2.5 times larger.

What impact will climate change have on boreal forests?

Will the warming feed the warming?

The answer to that question? It

depends, says Werner Kurz. (Policymakers get frustrated with that answer, he

says, but it’s true.) “From a scientific perspective there is huge uncertainty

about what the role of the boreal forests will be in future climate change.”

In some parts of the boreal, warming

temperatures, fewer frost-free days, and longer growing seasons could actually

make forests grow better. That would allow them to absorb more carbon dioxide

from the atmosphere and become better carbon sinks.

In other areas, thawing permafrost,

increased fires, pest outbreaks, and land-use change could all exacerbate the

release of greenhouse gases.

On balance, whether the increased growth will outweigh the negative effects – or vice versa – is incredibly hard to predict, says Kurz.

“We have a whole bunch of processes

that will be changing as a result of climate change. Many of these will enhance

growth, and many will accelerate decomposition – and frankly there is not a

scientist in the world right now that could claim with a straight face that

they could predict the outcome of these changes.”

Crucially, the risks are asymmetrical.

It can take a century for a forest to grow – and a matter of hours for it all

to go up in smoke.

“For boreal forest stands to reach maturity and maximum carbon storage, many decades of survivable growing conditions must prevail,” Kurz says. “But it only takes a single extreme event such as drought, fire, or insects to kill trees or whole forest stands.”

So what can be done?

Two things have to happen at the same

time, says Kurz, if we’re to avoid runaway climate change, and meet the goals

of the 2015 UN Paris Agreement to keep global temperature rise to less than two

degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

“We cannot do that without

simultaneously massive reductions in fossil fuel consumption, and managing the

land in such a way to contribute the greatest possible sink – so that it keeps

sucking carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere but also provides a continuous

supply of timber, fibre and energy to meet society’s demands.”

That means preventing forests from

becoming farmland or desert, fighting the fires and insects, and encouraging

local people’s involvement in protecting their forests.

Mongolia has taken up the challenge.

Alongside other efforts by the

national government, the country is also the first outside the tropics to begin

preparing for REDD+, an international climate change mitigation scheme under

the UNFCCC that aims to assist developing countries to protect their forests

and the carbon stores within them.

Khishigjargal Batjantsan grew up a

city boy in Ulaanbaatar, but spent his childhood summers in the countryside

with his herder grandparents, where he gathered blueberries and learnt what the

forests meant for herders.

Now, he’s the National Programme

Manager of the UN-REDD National Programme in Mongolia, which has been assisting

the country to develop the capacity needed to meet the requirements of REDD+.

“We have a long-standing relationship

with our natural ecosystems, including forests, because of our nomadic

traditions,” he says.

Mongolians established the first

national park in history, he points out – the sacred mountain Bogd Khan Uul was

declared a protected area in 1778, and there’s some evidence its protection

dates back even further, to the time of Genghis Khan in the 13th century – and

despite the rapid pace of change in the country, forests are still a key part

of Mongolians’ identity, Khishigjargal says.

The UN-REDD Programme will soon come

to an end, but the country’s REDD+ strategy will continue, he says. “In our

vision we aim to make Mongolia’s forests more resilient to climate change,

while supporting livelihoods and the wood industry."

That includes finding smarter ways to tackle fire and pest outbreaks, reducing the area affected by forest fires by 30 percent – and could also involve easing the restrictions on community groups’ use of the forest.

Khishigjargal believes that allowing

local people to harvest some timber will lead to better environmental outcomes.

Since the FUGs were established in the mid-1990s, he says, there has been a

reduction in both fires and illegal logging.

“But at the same time there’s not much

motivation for FUGs to protect their forests if they don’t have the right to use

it for certain purposes. At the moment it’s all responsibility, and few

rights.”

The idea is still controversial, and

Khishigjargal emphasises it would need to be tightly regulated. “Opening up the

forest has to be very carefully done, because once you do, if it’s not well

utilised it could lead to more deforestation.”

What’s important, says Oyunsanaa – who is also the National Programme Director of the UN-REDD Programme – is that scientists and policymakers, local people and NGOs, all work together towards a common goal.

“This is a

challenging time for us. We are a society in transition, and at the same time

the environment is rapidly changing, too. Climate change is

clear, and it is already influencing our people and our forests. We need more

detailed research into these connections, and we need to take action,

together,” said Oyunsanaa Byambasuren.

“This is a

challenging time for us. We are a society in transition, and at the same time

the environment is rapidly changing, too. Climate change is

clear, and it is already influencing our people and our forests. We need more

detailed research into these connections, and we need to take action,

together,” said Oyunsanaa Byambasuren.

In the valley outside Tunkhel, Baganatsooj the herder isn’t sure what the future holds. He would like his young son to follow in his footsteps. He wants to teach him the ways of the herder, just as his father taught him.

But his wife, Munkherdene, wants to

take the children to the city when they’re older, so they can get an education.

It’s a tough choice faced by traditional families all over Mongolia.

The old ways are becoming harder as

the climate gets harsher. Whatever they choose, Munkherdene is clear.

“Forests are essential for our life,” she says. “We should regenerate them and preserve them for our children – and the next generation after that.”

This story was prepared in 2018 by the

UN-REDD Programme and the Mongolia National UN-REDD Programme. It was made

possible through the generous support of the European Union and the governments

of Denmark, Japan, Luxembourg, Norway, Spain and Switzerland.

Ulaanbaatar

Ulaanbaatar