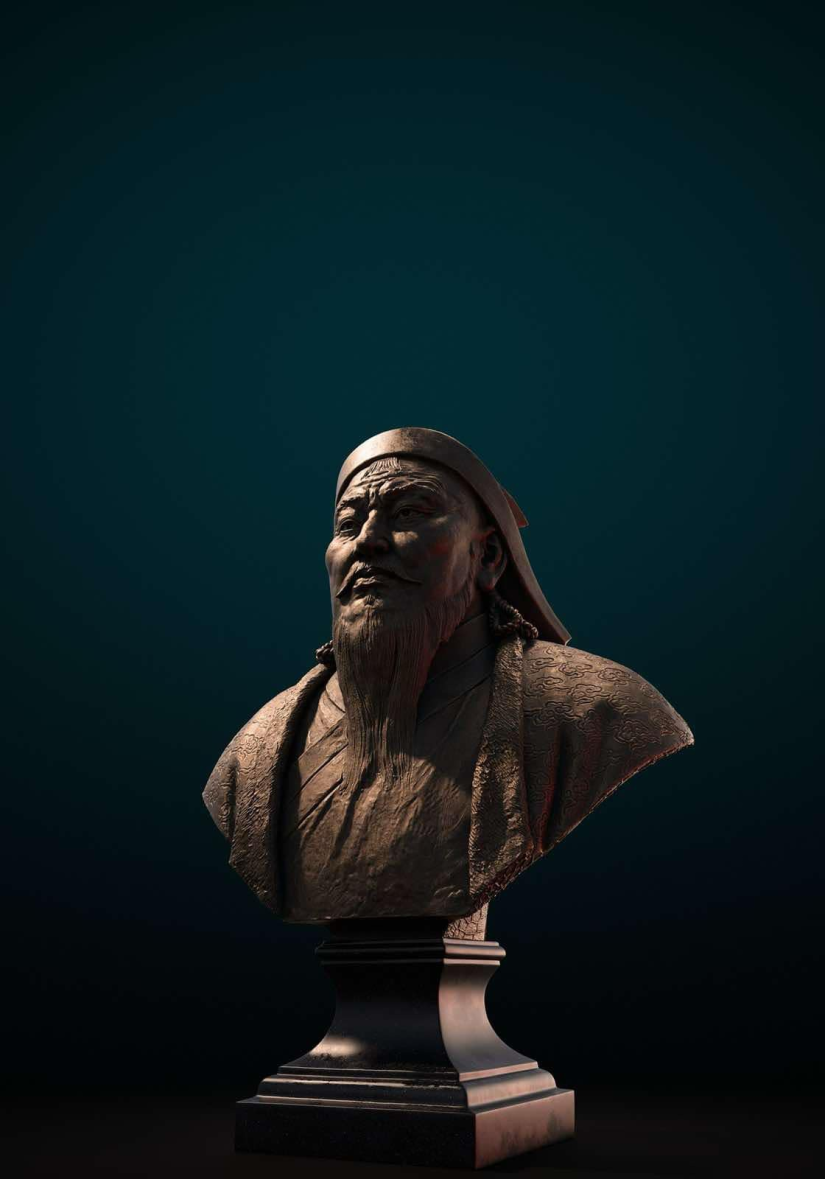

Chinggis Khaan: From Great Khaan to Venerated National Pride of the Mongols

Society

In the annals of world history, there is no figure quite like Chinggis Khaan — the most sacred figure of the Mongols, a unifying force, and a symbol of survival, revival, and cohesion for a people.

The Mongols, whether embracing Buddhism, communism, or liberalism, have always found a way to weave Chinggis Khaan into their cultural identity. Neither Buddha nor Marx could displace him. Prime Minister Genden once remarked, “In this vast world, two great luminaries were born: Chinggis Khaan and Buddha.”

In an era where ideology and civilization define nations, the Mongols’ national identity is undeniably anchored in Chinggis Khaan — and, of course, his successors, Ugudei and Khubilai Khaans. Chinggis Khaan laid the foundation of the Great Mongol Empire, Ugudei expanded it across the continents, and Khubilai stretched it to the seas. Together, they form a triumvirate of Mongol pride.

The Worship of the Great Khaans

After Chinggis Khaan’s ascension to the heavens in 1227, his descendants — Ugudei, Guyug, Munkh, and Khubilai — enshrined him as a deity, attributing their conquests to his divine will. The earliest records of this veneration come from European envoys like Benedict of Poland and Plano Carpini, who noted with a mix of awe and horror how the Mongols worshipped Chinggis Khaan’s effigy, offering daily sacrifices and executing those who dared disrespect it.

Khubilai Khaan, upon moving the empire’s capital to Khanbaliq and Shangdu, established the Eight White Yurts in 1263, which were dedicated to the worship of Chinggis Khaan and his successors. He commissioned portraits of Chinggis, Ugudei, and Tolui, ensuring their legacy was etched not just in history but in art. Though the details of these artistic endeavors are lost to time, one can imagine the meticulous care taken to capture the likenesses of these larger-than-life figures.

When the Yuan Dynasty fell in 1368, Toghon Tumur fled the capital, leaving behind the sacred portraits and relics of Chinggis Khaan — a poignant symbol of an empire in decline. Yet, even in the aftermath, the Mongols rebuilt the Eight White Urgoos [The Royal Chamber] in Ordos, enshrining Chinggis’s golden bow and arrow as sacred objects and continuing the rituals of enthronement before his spirit.

For the Mongols, Chinggis Khaan has been both a source of strength in times of triumph and a beacon of hope in moments of despair. The Eight White Urgoos stand as a testament to this enduring legacy — a reminder that, whether rising or falling, the Mongols have always drawn their unity and resilience from the Great Khaan.

The Sacred Figure Across Faiths

In the 16th century, as Buddhism spread across Mongolia, Chinggis Khaan was increasingly venerated as an incarnation of the Buddha. This syncretism not only elevated Chinggis Khaan to divine status but also facilitated the widespread adoption of Buddhism among the Mongols. By the 17th century, Mongol chronicles were describing Chinggis Khaan as a reincarnation of Vajrapani, a bodhisattva who unified the Mongol lands and ruled over the world with divine authority. The fusion of Chinggis Khaan’s legacy with Buddhist practices ensured that the Great Khaan remained at the heart of Mongol spirituality, even as the nation’s religious landscape evolved.

Communism, when it arrived in Mongolia, sought to erase Chinggis Khaan from the national consciousness. Yet, even as the Mongols embraced Marxist ideology, they never placed Marx above the Great Chinggis Khaan. For the Mongols, Chinggis Khaan was not just a historical figure but a source of identity—one that even the weight of Soviet ideology could not fully suppress.

The Eternal Pride

In recent years, Chinggis Khaan has re-emerged as a unifying symbol for Mongolia. President of Mongolia Khurelsukh Ukhnaa has overseen the installation of the golden and gilded Statues of Chinggis Khaan in museums, while artists like J. Tumenchuluun and T. Odon have created lifelike portraits of Chinggis Khaan, Ugudei Khaan, and Khubilai Khaan, drawing inspiration from historical sources and Yuan Dynasty artworks. These efforts are not merely acts of historical preservation but a reaffirmation of Mongol identity in a world grappling with geopolitical and ideological tensions. In a time of division, the legacy of the Great Khaans offers a reminder of unity, ambition, and resilience — a timely message for a nation navigating the complexities of the modern era.

Mongol Khaan Theatre LLC

Улаанбаатар

Улаанбаатар